Robin Hood and the Bishop of Hereford,

A story for May Day *

It happened that on the first day of May the Lord Bishop of Hereford was riding through the Great Greenwood that once covered most of England, on his way from the Abbey of St Hilda in Whitby to his own city of Hereford. Against the advice of the Abbot of Whitby, he was riding alone, for the Bishop was a man of great stature and courage and feared no man. “Besides,” he had said to the abbot, “who would waylay a man of the Church?”

As the Lord Bishop rode through the forest, looking around at the fresh, spring leaves on the oaks, the ashes, and the bonny rowans, and listening to the chaffinches giving their celebratory spring call and the jays laughing at them from deep in the trees, he too was filled with joy, and broke into a chant, in the manner of St Gregory.

“Te Deum laudamus,” he sang, in his great baritone. “Te Dominum confitemur…” and the birds seemed to increase their trilling and laughing in friendly rivalry with him. Here, where the forest was at its deepest and greenest, and the track wound in between the oak boles, he felt was a place of goodness, where no harm could come to anyone, and if anywhere was a remnant of the blessed Garden of Eden, then this corner of England was it.

“Hold!” cried a voice, of a sudden. The Bishop broke off his song, looked down, and saw that he was surrounded by men in Lincoln Green, one of whom – a bold, smiling villain in a feathered cap – held fast his palfrey’s bridle. All brandished stout longbows with arrows nocked, some of which were pointed at him.

“Who are you men who roughly and rudely interrupt my praises to the Almighty, prevent my travel, and disturb this blessed Spring day?” cried the Bishop. “And especially, who art thou, grinning in thy beard? Yes, thou, the knave with the pheasant’s tail in his bonnet, who hast laid hands on my horse.”

This man, who appeared to be the leader of the troop, let go of the bridle, showed the palm of his hand to be clear of it.

“Upon your parole, then, my Lord Bishop,” he said. Then, sweeping his cap from his head, he bowed low and made a respectful leg to the prelate. “I am known in these parts as Robin Hood, and these honest churls, on whose behalf I beg your pardon for the interruption to your journey, are my friends and fellow Foresters. We collect the toll from travellers who pass this way.”

“Never let it be said that I refused to render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s,” said the Bishop. “How much is the toll?”

“Half of all you carry,” said Robin, “and an hour or so of your time to dine with us.”

The Bishop’s eyes opened wide. “I am a humble priest!” he protested, “but even half of what I carry is too much to ask, surely?”

“Your fine garments, your riding-horse, the ring on your finger, and the heavy pouch at your belt would all say that you are far from humble, My Lord Bishop. Besides, it is much less of an impost than some of my men here have had to pay, having lost all they ever possessed.”

Now the Bishop, large and fearless though he was and capable of standing a round of buffets with any man, was kindly at heart. He had heard of how the outlaws of Sherwood, once they had sufficient to keep themselves fed, would distribute the bulk of their pelf to the poor, and he himself was cognizant of the virtue of St Martin. He recalled the story of how the saint, while still a soldier and a worldly man, had freely cut his paenula in two and given half to a shivering beggar who – as it was revealed to him in a dream – was Christ in disguise. Well, the man with the feathered cap was no Christ, any more than the others of the green-clad band were Apostles, so the Bishop was of a mind to have some sport with them.

“I doubt me, Sirrah, that thou art truly Robin Hood,” he said. “And if thou art not, what is to prevent another band of robbers stopping me a mile hence with their own claim to be the Merry Men of Sherwood, then another band a mile further, then another and another, each taking half, until I am left with a groat, half a cassock, half a cloak, and one shoe? I hear that Robin Hood and his followers are great archers. Lend me for one minute one of your longbows – let it be the worst you have – and I shall loose an arrow, shooting it as far as I can. If you can shoot further, and thou, Feathered-Cap Esquire, furthest, then I shall acknowledge that I am indeed in the presence of Robin Hood and his men, and I shall pay the forest-toll.”

With these words the Bishop leapt down from his horse and took hold of the bow of Much the Miller’s son, nocked an arrow to it, drew it, and let fly. The arrow’s flight was long, and it landed in a field beyond the trees. The Bishop handed the bow back to Much, who nocked a second arrow, drew back the bowstring, and with a grunt of effort shot it into the same field, but a little further than the Bishop’s. The Bishop clapped his hands.

“Excellent bowmanship for such a young lad!” he exclaimed, and then pointed at Will Scatlock. “Now this fellow!”

Will drew back his bowstring and shot an arrow into the next field, to the Bishop’s delight. Each of the band had his turn, each shooting further and further, until it was the turn of the tall, powerful John Little. With his mighty arms he drew back his bow and loosed an arrow that went two fields further than the last man’s.

“Thou giant!” cried the Bishop, even though he was of a height with John Little. “I’ll wager no one can best that!”

Robin Hood stepped forward. He was no match for his great lieutenant in height and strength, but his skill was such that he knew well how to make the most of a longbow. He took his bow, nocked an arrow, drew, elevated the bow with exactness and, having waited for the wind to die a little, let fly. The arrow went a prodigious distance and landed one field further than John Little’s. The Bishop clapped and cheered, and then bowed to Robin, addressing him politely.

“You are indeed Robin Hood!” he said. “That I freely acknowledge.”

“Then pay the toll, my Lord Bishop,” said Robin. “That was the wager.” But the Bishop mounted his horse again and raised an eyebrow in a pretence of haughtiness.

“Who is to stop me? All your arrows are spent!”

Robin saw that the Bishop had bettered him, and he threw back his head and laughed. Then he bowed again.

“Well won, Well won! The freedom of the forest track is yours. Pass onwards free of toll, for you have taught us all a lesson today, and that is worth more than any toll.”

But the Bishop did not spur his horse. “I am determined to be magnanimous in victory,” he said. “These lands hereabouts are mine, and the field where the lad’s arrow landed I shall give to him, and it shall be known as ‘Miller’s Field’. The next, where Scatlock’s arrow landed, shall be his and shall be called ‘Will Scatlock’s Field’. And there shall be ‘John Little’s Field’, and ‘Robin’s Field’, and a field for all of you.” And this offer was a true one, because the Bishop was not only a priest but also a great holder of land in his own right, being of the line of one of the Conqueror’s barons.

“Alas,” said Robin, shaking his head, “ this cannot be, for we are outlaws and forbidden to hold land.”

“Some say, however, that you are heir to the Manor of Locksley.”

“Aye, and others that I am the son of the Earl of Huntingdon, and others still that I am a Knight of the Cross of St John. But the law is the law, and we are outside it,” said Robin.

The Bishop dismounted again and clasped Robin’s hand.

“Then your lineage,” he said, smiling, “matters nothing to me. We shall halve the contents of my purse. Now, I believe there was some mention of dining – dare I expect venison?”

Thus the Bishop of Hereford came to feast in Sherwood, and a merry May Day was had by all. The Bishop counted over half of the coins in his purse, as he had promised, and made sure he had at least his fair share of venison. He conversed in Latin with the good Friar Tuck, in French with Demoiselle Marianne who was Norman, and even in Arabic and Greek with ibn Hassan, Robin’s hostage-become-friend. At the end of the feast he went on his way with many a wave and a Pax Vobiscum.

From that day, in all the diocese of Hereford, no church from the Cathedral itself to the lowliest chapel would refuse sanctuary to any man dressed in Lincoln Green; and every May Day was a holiday amongst the outlaws, and in their feasting they never forgot to toast the Bishop of Hereford, the only man ever to get the better of bold Robin Hood.

__________

* In most of the Robin Hood folk-tales, the Bishop of Hereford is portrayed as an enemy of Robin and the outlaws. In this particular tale, which is based on a story I heard from a teacher when I was a little girl, the Bishop is a good character. This tale is retold just for fun, without any pretended literary merit – whoever heard of a folk tale having literary merit, for heaven’s sake!

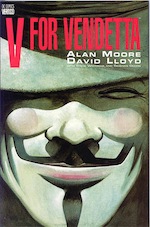

I own only one graphic novel, Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta. Of course I do – why wouldn’t I own a book in which an anarchist superhero goes mano a mano with a fascist government in Britain? I notice that Alan Moore distanced himself from the film version, exciting though that was (and it starred the wonderful Hugo Weaving!), saying that it had been ‘turned into a Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country’. Having read the script, he said,

I own only one graphic novel, Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta. Of course I do – why wouldn’t I own a book in which an anarchist superhero goes mano a mano with a fascist government in Britain? I notice that Alan Moore distanced himself from the film version, exciting though that was (and it starred the wonderful Hugo Weaving!), saying that it had been ‘turned into a Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country’. Having read the script, he said, Kick Ass is fun. It came in for a lot of abuse on account of the bad language, less for the violence – with the exception of one teenager, no bad guy is left alive by the end of the film. Its killing-spree violence is in the tradition of Peckinpah and Tarantino, subverting the bloodless wrong-righting of The Lone Ranger and Batman. I think people missed the point that it is highly satirical of the superhero genre, and simply spares no effort to de-bunk its ‘zap’ and ‘pow’ fisticuffs. It is, as the cover of the comic book says ‘Sickening violence, just the way you like it’, signaling that it does not take itself seriously and shouldn’t be taken too seriously by readers and movie-goers. The satire of the film is taken further by the character Big Daddy (Nicolas Cage) adopting the phrasing of

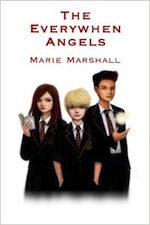

Kick Ass is fun. It came in for a lot of abuse on account of the bad language, less for the violence – with the exception of one teenager, no bad guy is left alive by the end of the film. Its killing-spree violence is in the tradition of Peckinpah and Tarantino, subverting the bloodless wrong-righting of The Lone Ranger and Batman. I think people missed the point that it is highly satirical of the superhero genre, and simply spares no effort to de-bunk its ‘zap’ and ‘pow’ fisticuffs. It is, as the cover of the comic book says ‘Sickening violence, just the way you like it’, signaling that it does not take itself seriously and shouldn’t be taken too seriously by readers and movie-goers. The satire of the film is taken further by the character Big Daddy (Nicolas Cage) adopting the phrasing of  Having fallen almost by accident into writing for young adults, I find myself skirting superhero territory. The teenagers in my novel The Everywhen Angels have powers that they don’t quite understand, and the protagonist in my recently-completed teen-vampire novella, From My Cold, Undead Hand, is a girl who has been trained to hunt and destroy vampires. Consciously or unconsciously, however, I seem to have made these characters break a mould, or break out of a strait-jacket. Unlike traditional heroes, they don’t necessarily win, they don’t necessarily triumph over a force bigger than they are, their tales do not have a clear resolution where all is explained in a neat and tidy way. Good does not necessarily triumph over evil, and where it does it may well be by accident rather than design. Why?

Having fallen almost by accident into writing for young adults, I find myself skirting superhero territory. The teenagers in my novel The Everywhen Angels have powers that they don’t quite understand, and the protagonist in my recently-completed teen-vampire novella, From My Cold, Undead Hand, is a girl who has been trained to hunt and destroy vampires. Consciously or unconsciously, however, I seem to have made these characters break a mould, or break out of a strait-jacket. Unlike traditional heroes, they don’t necessarily win, they don’t necessarily triumph over a force bigger than they are, their tales do not have a clear resolution where all is explained in a neat and tidy way. Good does not necessarily triumph over evil, and where it does it may well be by accident rather than design. Why?