The Emerald…

… the story of the last Scotsman in the universe!

I met the last Scotsman in the universe in a bar on Cargo, a hole of a planet about sixteen jumps from Galactic Home. You can’t get much further away. There’s only one more jump in that direction, and that drops you by a cluster of unimpressive, wobbly rocks on the edge of a supervoid. Cargo isn’t a whole lot more impressive than that, it’s just a planet where people dump stuff, stuff that might, or might not, go on to the prospecting stations on Coral or Juke, the two other planets in the same system. Anyhow, that’s where I met him. Mack Gregor Elcho was what he called himself. He was much like any of us that turn up in such places – those of us with a shred of dignity try to smarten up our one suit, our one shirt, our one pair of dirtboots, and those without don’t. I guess Mack Gregor Elcho was on the cusp. He had a beard, because he said all Scotsmen had beards, and he wore a skirt woven from some obscure sideworld fibre. He carried his scrip, which he kept fingering and shifting, on a hide thong round his neck. His eyes, when he bothered to hold your gaze, seemed to have a cold fear lurking in them, as though he was not only on the cusp of desperation there on Cargo, but also of insanity.

And he had an emerald.

He showed it to me. It fitted into the palm of his hand. I had never seen an emerald as big as that in my life, not anywhere, not even on Gemstone Five, not even in the markets and bazaars of Jackson’s Moon, not even in the crown of the Merovingian Queens in the Great Museum of Innsmouth City on End-All. I wondered why the hell he held onto it – and oh brother did he hold onto it! – why he didn’t sell it, buy himself a handsome skirt and scrip and dirtboots and book a jump back to civilisation. But he didn’t. He showed it to me for a brief second, then closed his fist on it again, and it winked at me, deep green, between his fingers. I couldn’t keep my eyes of that glint of deep green, and he knew it.

“Buy us both a drink, laddie,” he said in his strange accent, “and I’ll tell you all about it.”

That was an invitation hard to resist, so I didn’t resist it. I weighed up the few roundels of base metal that I had, the dull discs that pass for currency out there on Cargo, and blew them on a shot of hard liquor for us both. I pushed his over to him, and told him to go on. He did. Thus.

“Laddie, I was the last man to leave the planet of Scotland. It’s a world that has some kind of curse on it, for folk either worked themselves to death under its blue sun, or died young of despair, or left as soon as they had siller enough to their credit. All who left, few enough of them at the end, gave up the name of Scotsman, gave up our lingo, gave up our names and our way of dressing. Where they are now, who can say? I’m the last one to keep his Scotland name, the last one with tales and songs of the old place, the last man to wear skirt and scrip.”

“I had a place kept for me on the very last evacuation jumper, and if I did not take it, I would be marooned there for ever. But I had to make one last quest. I had heard a tale… in a bar much like this except that the owner was nailing boards over the windows and pouring the last of his liquor into glasses for us last-gaspers… of this emerald. This very emerald. It was to be found, I was told, way off in the jungle, in a castle called Elcho. Yes, a castle with my name on it! How could I resist? I fuelled and provisioned an abandoned, ramshackle skimmer and, despite the protests of the other last-gaspers and of the Captain of the jumper who said he would not wait for me, I set off along the coast towards where the castle supposedly lay. I skimmed until I found the mouth of the bronze, oily river Tay, where it spews its metallic water into the sea. There I turned inland, and wound my way along the river, as the grey jungle closed in on me. To one side the great Kinnoull Volcano rose, filling the air with acrid dust, choking the filter of my mask and fogging my visor. I knew that the castle was to be found on the other side of river, and from time to time I had tantalising glimpses of something rising above the great ferns and weeds that made up the jungle, but as soon as I caught sight of it there would be a bend in the river, or a higher patch of vegetation, or a drift of smoke and dust from Kinnoull, and it would disappear again.”

“At last I figured that I must be close enough to it to attempt a landing. That wasn’t easy, as the jungle didn’t just grow down to the Tay, it overhung it. Tendrils hung down that looked as though they might snake out to grab, and things moved and rustled in the overhanging limbs and stems. But I found somewhere where the ferns and weeds had died back, and I cut the skimmer’s drive and beached it there. Walking on the dead vegetation was like walking on corpses, stepping on what felt like human arms and legs. Something told me to go back to the skimmer, to get out of there and join the others on the jumper. But equally something – greed, I guess, and stubborn curiosity – drove me on. Keep in mind, laddie, that these two feelings pulled and tugged at me all the time. I cut through the living jungle with a small plasma-spade, using it like an axe, leaving a fingertip-to-fingertip trail behind me, ignoring the scuttling and snarling in the untouched vegetation. I don’t know how long I kept this up, but it got to the point I was sure that the charge in the spade was about to give out and I would never find the castle. I was close to despair at that point, the tears of frustration being the only thing to wash the sweat out of my stinging eyes, when suddenly the grey ferns gave way, and I came out into a clearing. It was a place of bare, hard, blue dirt, as though the jungle somehow didn’t dare grow there. And in the centre of it stood Elcho Castle.”

“It was a ziggurat of grey-blue stone, with a way – part ramp, part stair – that wound upwards to the topstone, in which an apparent doorway gaped. The air was heavy and still. Even the dust from the volcano seemed to shy away from this place. As I climbed the sloping path cut into the side of the castle, I was aware of the eroded carvings on the walls. Figures seemed to dance, to bow, sometimes to stand erect like guards; but all seemed to be gesturing upwards, urging me on. It felt as though these figures had been waiting for no one but me to come here and climb this winding path. But this was a structure unlike anything I had ever seen on Scotland. It was unlike the castles and granaries and towns that generations of Scotsmen had built in the south, since the planet had first been peopled. It seemed to be made of living stone, not of Scotland Iron and off-world concrete like any civilized building had been until everything had started to crumble from neglect. It was old, far older than our generations. It felt durable, almost eternal. The erosion spoke to me of not of centuries but of millennia, or of hundreds of millennia. Who had built it? What civilisation had been here before the first Scotsman? What people had they been, who had left no other trace on the planet apart from this everlasting place?”

“It was a ziggurat of grey-blue stone, with a way – part ramp, part stair – that wound upwards to the topstone, in which an apparent doorway gaped. The air was heavy and still. Even the dust from the volcano seemed to shy away from this place. As I climbed the sloping path cut into the side of the castle, I was aware of the eroded carvings on the walls. Figures seemed to dance, to bow, sometimes to stand erect like guards; but all seemed to be gesturing upwards, urging me on. It felt as though these figures had been waiting for no one but me to come here and climb this winding path. But this was a structure unlike anything I had ever seen on Scotland. It was unlike the castles and granaries and towns that generations of Scotsmen had built in the south, since the planet had first been peopled. It seemed to be made of living stone, not of Scotland Iron and off-world concrete like any civilized building had been until everything had started to crumble from neglect. It was old, far older than our generations. It felt durable, almost eternal. The erosion spoke to me of not of centuries but of millennia, or of hundreds of millennia. Who had built it? What civilisation had been here before the first Scotsman? What people had they been, who had left no other trace on the planet apart from this everlasting place?”

“When I reached the topstone, the final stupa, and stood before the dark maw of the opening I had seen, I hesitated. The fear I had felt urging me to go back was now stronger than ever. But also that insatiable feeling that I should go on had increased. I gripped my spade, hit the on-button again to make it into a torch to see by, and stepped inside the chamber. I was surprised to find that I didn’t need any extra light. Something in there was making its own illumination. At the far end of the chamber something was glowing green. It was this emerald. The story had been true.”

“I stepped towards it, and found myself teetering on the edge of a void, my right foot swaying over black nothingness. I had been so intent on the emerald that I had not seen an opening in the floor. Sweat streamed down my body, prickling as it ran. Whimpering in fright, I sat down on the lip of the opening. I cried, I laughed, sanity slipped away a little as I realised how close to death I had come, rather than to a fortune. Recovering myself after a few minutes, I picked my way carefully round the opening, until I reached the emerald. I had thought it might have been fixed somehow, but in fact it lay cupped in a hollowed-out niche in the stone. All I had to do was to pick it up. And I did just that.”

“Laddie, it continued to glow. It threw a light onto the walls. There were carvings there, just like those on the outside, but less worn. They beckoned and gestured, but not upwards this time, rather they pointed towards the opening in the floor, in which I saw steps leading down. As though under an unspoken obligation or command, I held up the glowing emerald and walked down into the interior of the castle. I reached the first level down, where I stopped, held up the emerald, and looked around. Beams from the jewel shone onto the carvings on the wall. Before my eyes was an incredible scene. It was the meeting of two races. One race, the hosts, had faces that were like the lemurs of Azimov Seven, dog-like, mouths turned up in smiles. They were bowing in welcome, honouring an embassy from a second race. Tall, erect, proud, the second race was unmistakably… human. I walked round and round this level, taking in the details of the carving, studying, making mental notes, imagining myself stopping the flight of the last jumper and leading an expedition back here to study this archaeological marvel. A fascination had almost swept away my fear. But then something caught my attention. I held the emerald close and looked intently at the lemur-faced people. There was something sly in their eyes, there were backward glances, furtive looks shared with each other, their smiles seemed suddenly less those of welcoming hosts, but more of smirking conspirators. My fear returned. What was I seeing?”

“Ah, but don’t think that fascination died, laddie! I could see another opening in the floor, and another set of steps leading down. I followed them – what else could I do? – into the second level down. In a chamber larger than the last, the walls had carvings of the lemur-people setting a great feast before the human ambassadors. They brought to their seated guests great chargers full of food, goblets of drink. They waited upon their guests with courteous bows. They toasted their guests and were toasted in turn. The guests sat and reclined at their ease. As they consumed the feast, a troupe of lemur-women danced for them. It seemed a noble celebration. But again in the eyes of the lemur-folk were the same knowing, conspiratorial glances. I wanted to warn the human guests that they were in some kind of danger, but how could I warn figures of stone?”

“The walls of the third level down made me gape. The feast had been cleared away. The lemur-people were now debauching their guests, coupling with them, mating with them, pleasuring their bodies. And still… still… those smug looks of conspiracy passed between them. It was as though the lemur-people themselves had made these carvings themselves, to show how clever they were. Or maybe some third race was responsible for this show, and had placed the carvings here as a warning. But why, and to whom? I was, as far as I knew, the only human ever to have set eyes on them. I can tell you, laddie, it was with my heart in my mouth that I went a further level down. Aye, I did, though…”

“The walls of the fourth level… how can I tell you how the sight of them paralysed me, how that prickle of terror broke out all over me again. By the light of the emerald this is what I saw.”

Mack Gregor Elcho took a breath, a swig of his liquor, and went on.

“On the walls of the fourth level, laddie, the conspiracy had been launched. The human guests, where they had sprawled in lust, were now trapped, pinioned, bound. They were being subjected to all kinds of torture at the hands of the lemur-folk, who sunk teeth and claws into them, pierced them with instruments of torment. The humans’ faces were contorted in a rictus of agony, or frozen in screams. They writhed, struggling to escape, but impotent to do so. It was a scene of total horror, and it was made more horrible by the smug satisfaction in the faces of the lemur-people.”

He paused again, picking up his glass and looking at it but not drinking from it. His other hand clutched the emerald as tightly as ever. I broke the silence and said that I imagined he would now tell me what was on the fifth level down. He sighed, and with his eyes still on his glass, he went on.

“Laddie, you have no idea how I have tried to hide behind glasses, and bottles, and needles, and tokes, and cyber-probes, and every trick known to sentient beings, short of suicide, to eradicate from my head the nightmares I have every time I shut my eyes. Every sleep-cycle they come, and they won’t stop. Yes, yes there was a fifth level, and I looked down into it, laddie. I didn’t go down, otherwise… well… who knows. But I looked into it. And do you want to know what I saw? I saw… moving down there… tormented and tormenting, locked into an eternal scene of torture, the writhing, agonized humans, and the lemur-folk reveling in their pain, rending them with teeth, claws, knives, complicated instruments, licking their blood!”

“I have no idea how, but I must have climbed back into the daylight, fled from that unholy place back down the path I had cut through the jungle, not caring about any danger from jungle creatures or the hanging tendrils of predatory plants. I must have piloted the skimmer back to the jumper port. I vaguely recall hands tugging me inside the last open hatchway and the hatch slamming shut behind me. When at last I came to my senses, I was three jumps past Scotland, lying in a filthy bunk, my right hand buried deep under my tattered clothes, clutching this emerald in my fist.”

The self-styled last Scotsman in the universe stopped, pausing for a long time, fixing me with a gaze that was watery but piercing.

“Do you believe me?” he asked.

I took a deep breath.

“No. No, I don’t believe you. I don’t believe a word!” I said loudly, pushing myself back in my chair. “For a start, who could have told you about the emerald except someone who had already been there? Why didn’t this person take the jewel for himself? No, I don’t believe you! There’s no such planet as Scotland, no such river, no such jungle, no such volcano, no such castle. If there were, you would take back your lousy emerald and leave it where you found it. If it is an emerald at all. Look at you, you’re a space-tramp, a derry, a has-been. If that was a real emerald you would be a rich man with a jumper of your own, not some old chavo in a skirt and scrip begging drinks in bars. It’s a worthless piece of glass, and you’re trying to get me to buy it, or something like that. Last Scotsman in the universe – ha! ”

He waved his fist in front of my face, the jewel still glinting between his fingers.

“Oh it’s true right enough,” he said. “Every last word is true. But I can’t put it back, and I can’t sell it. Laddie, you believe me… I can see it… you believe me!”

“No, no!” I yelled. “I don’t believe you!”

But I did, you see. I believed it all, from beginning to end. That is why, I guess, the last I knew of Mack Gregor Elcho was the swish of the airlock of that bar on the planet Cargo as he left. And this emerald tight in my fist. That’s what my belief brought me. That and his nightmares. Every sleep-cycle I take every step of his journey, I live it, I live every moment. I am myself, if you like, now the last Scotsman in the universe, and my own name, the one I have carried throughout the whole of space from one end to the other, is scarcely relevant. I know, sure as I know my own unshaven face in a mirror, the same bronze, oily river, the same volcano, the same jungle, the same planet Scotland. And the same dreadful ziggurat of blue stone under a blue sun, in which, in sleep after sleep, I see the same proud human embassy debauched, seized, and tortured by the lemur-people, the same blood, the same agony. Oh brother, the torture in my mind is as great as theirs. It’s eternal, it never stops. And it’s all as true as true can be, it’s as true as this emerald you see winking in my hand, as true as its green light, as true as its awful fire that reveals what should never be revealed, the truth at the heart of that cursed planet, Scotland…

Hey… buy me a drink now. And hey… do you believe me?

Do you believe me?

Do you?

There’s a lot that can be said about the Burning Man festival, held every year in the Nevada desert, and not all of it is positive. But the one thing that I support is that its internal function depends on everything being free – not bought and sold, not even bartered, but free. Everything is, somehow, paid on. Now, of course I don’t attend, for many, many practical reasons, but this year I have had a remote presence. Not only did I write the script for the Guild History of I Tamburisiti di FIREnze, as posted here before, but I also provided some poetry for display there.

There’s a lot that can be said about the Burning Man festival, held every year in the Nevada desert, and not all of it is positive. But the one thing that I support is that its internal function depends on everything being free – not bought and sold, not even bartered, but free. Everything is, somehow, paid on. Now, of course I don’t attend, for many, many practical reasons, but this year I have had a remote presence. Not only did I write the script for the Guild History of I Tamburisiti di FIREnze, as posted here before, but I also provided some poetry for display there.

I told you in

I told you in

This year the theme is The Renaissance. I was contacted a few days ago by the Project Coordinator of ‘Camp Thump Thump’, a group that regularly attends Burning Man, giving lessons in drum-making and drumming, letting people build, play, and take away their own drums. For 2016 the group has adopted a theme based on renaissance Italy – the time of the Borgias, the Medici, and Leonardo da Vinci – and have reinvented themselves as

This year the theme is The Renaissance. I was contacted a few days ago by the Project Coordinator of ‘Camp Thump Thump’, a group that regularly attends Burning Man, giving lessons in drum-making and drumming, letting people build, play, and take away their own drums. For 2016 the group has adopted a theme based on renaissance Italy – the time of the Borgias, the Medici, and Leonardo da Vinci – and have reinvented themselves as  The Sun came to the Earth and had a child with her. That child was a field of wheat, and it grew from its mother towards its father, becoming more and more golden.

The Sun came to the Earth and had a child with her. That child was a field of wheat, and it grew from its mother towards its father, becoming more and more golden. missed. So the Sun and the Earth called upon their friends the Four Winds, and together they made seasons to nourish all that was left of the wheat-child. And eventually that single stalk of wheat became a great Tree.

missed. So the Sun and the Earth called upon their friends the Four Winds, and together they made seasons to nourish all that was left of the wheat-child. And eventually that single stalk of wheat became a great Tree. It happened that War saw a beautiful woman, whose name was Peace. Desiring her, he took her away to live with him. But Peace was never happy, and when he asked her why, she answered that it was because she was cold, for though War is hot he can never pass his warmth on to anyone.

It happened that War saw a beautiful woman, whose name was Peace. Desiring her, he took her away to live with him. But Peace was never happy, and when he asked her why, she answered that it was because she was cold, for though War is hot he can never pass his warmth on to anyone.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” says Prospero at the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the euphony of that phrase of feminine-ended tetrameter shines out of the dark of four centuries, reminding the audience of the essentially ephemeral existence of that redemptive fantasy and its characters.* Shakespeare was a genius of language; it was all he had to hold his audience with, in the days when CGI effects were not even dreamt of. And this phrase, shining like a candle, ends with a preposition.

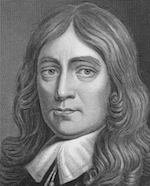

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” says Prospero at the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the euphony of that phrase of feminine-ended tetrameter shines out of the dark of four centuries, reminding the audience of the essentially ephemeral existence of that redemptive fantasy and its characters.* Shakespeare was a genius of language; it was all he had to hold his audience with, in the days when CGI effects were not even dreamt of. And this phrase, shining like a candle, ends with a preposition. So, where did the rule to the contrary come from? Many consider that the attribution of Shakespeare’s usages not to one-part-observation one-part-inventiveness, but to ignorance and lack of education, started with John Dryden in the late 17c. Dryden was a scholar of Latin, and since in Latin it was impossible to end a sentence with a preposition, he decided it should be improper in English, usage or no usage.** Influential amongst his own circle though Dryden might have been, ‘Dryden’s Rule’ was not codified until the second half of the 18c, when Bishop Robert Lowth produced his A Short Introduction to English Grammar.

So, where did the rule to the contrary come from? Many consider that the attribution of Shakespeare’s usages not to one-part-observation one-part-inventiveness, but to ignorance and lack of education, started with John Dryden in the late 17c. Dryden was a scholar of Latin, and since in Latin it was impossible to end a sentence with a preposition, he decided it should be improper in English, usage or no usage.** Influential amongst his own circle though Dryden might have been, ‘Dryden’s Rule’ was not codified until the second half of the 18c, when Bishop Robert Lowth produced his A Short Introduction to English Grammar.  But even he acknowledged that ending a sentence with a preposition was dominant ‘in common conversation’ and suited ‘very well the familiar style of writing.’ So not even Lowth would go as far as saying it should never be done!

But even he acknowledged that ending a sentence with a preposition was dominant ‘in common conversation’ and suited ‘very well the familiar style of writing.’ So not even Lowth would go as far as saying it should never be done! At this point in the discussion of prepositions it is usual to cite Winston Spencer Churchill who, it is supposed, replied to a torturous memo from a civil servant, in which prepositions had been engineered away from the end of phrases to the extent that the prose resembled crazy-paving, ‘This is something up with which I will not put!’ However, nice though this piece of ridicule is, the story is apocryphal.

At this point in the discussion of prepositions it is usual to cite Winston Spencer Churchill who, it is supposed, replied to a torturous memo from a civil servant, in which prepositions had been engineered away from the end of phrases to the extent that the prose resembled crazy-paving, ‘This is something up with which I will not put!’ However, nice though this piece of ridicule is, the story is apocryphal. Equally, when Abraham Lincoln drew the preposition away from the end of a sentence in his address at Gettysburg – ‘increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion’ – he knew precisely where the emphasis should fall in his rhetoric. Thus both are correct, in their own way, according to the context.

Equally, when Abraham Lincoln drew the preposition away from the end of a sentence in his address at Gettysburg – ‘increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion’ – he knew precisely where the emphasis should fall in his rhetoric. Thus both are correct, in their own way, according to the context. There is, of course the question of using a double negative as an intensifier. Now, do I need to quote Shakespeare and Milton to anyone? It is usual for anyone who hears a usage in English that they think is ugly, ‘lazy’, or just new, to shake their head, wring their hands, and lament “Oh, the language of Shakespeare and Milton!” The thing is, both of these writers sometimes used double negatives as intensifiers. Oh yes they did!

There is, of course the question of using a double negative as an intensifier. Now, do I need to quote Shakespeare and Milton to anyone? It is usual for anyone who hears a usage in English that they think is ugly, ‘lazy’, or just new, to shake their head, wring their hands, and lament “Oh, the language of Shakespeare and Milton!” The thing is, both of these writers sometimes used double negatives as intensifiers. Oh yes they did! In AAVE, as I said, the use of a double negative as an intensifier is very common. So, for example, when Ray Charles sang “I don’t need no doctor…” it was perfectly clear what he meant. Again – clarity. But my stubborn blogger again could not get his head round the fact that to use or not to use a double negative depended entirely on context, not on a supposed laziness or lack of education. Certainly not on my part.

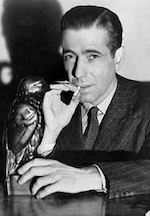

In AAVE, as I said, the use of a double negative as an intensifier is very common. So, for example, when Ray Charles sang “I don’t need no doctor…” it was perfectly clear what he meant. Again – clarity. But my stubborn blogger again could not get his head round the fact that to use or not to use a double negative depended entirely on context, not on a supposed laziness or lack of education. Certainly not on my part. * Humphrey Bogart’s final words in The Maltese Falcon – “The stuff that dreams are made of” – is in fact a misquotation. But that isn’t a problem, because there are many, many misquotes from Shakespeare, from the Bible, from other sources, floating freely out there. The English language is not poorer for them, it is probably richer.

* Humphrey Bogart’s final words in The Maltese Falcon – “The stuff that dreams are made of” – is in fact a misquotation. But that isn’t a problem, because there are many, many misquotes from Shakespeare, from the Bible, from other sources, floating freely out there. The English language is not poorer for them, it is probably richer.