How Tam o’ Shanter came to be written – a tale for Burns Night

Was it a year ago now, since last we piped in the great chieftain o’ the pudding race, that we raised an amber dram, that we all gave a hearty slainte mhath! There was one braw lad whose eyes were twinkling with glee and single malt, who rose and recited – without a prompt – the auld tale of Tam o’ Shanter, the skellum the blethering, blustering, drunken blellum. Aye, aye, and how we laughed, how we all chorused “Weel done, Cutty Sark!” And how we cheered on old Tam was he whipped Maggie his mare towards Doon Water and the Brig, held our breath at the last loup of Nannie the witch to grab the mare’s tale as Tam won to the key-stane o’ the brig, and yes, how we let it all out with a big gasp when he was hame and free. More, how we winked and smiled and nodded at each other when our impromptu Makar wagged his finger and said:

Noo, wha this tale o’ truth shall read.

Ilk man and mother’s son, take heed;

Whene’er to drink you are inclined,

Or cutty sarks run in your mind,

Think! Ye may buy joys o’er dear –

Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mare.

Aye, aye, and we clapped and cheered of course, and shouted out, “More! More!” – and of course there is no more, for no one, least of all our national Bard, ever wrote The Further Adventures of Tam o’ Shanter. But of course the moment passed, and then someone got up and sang My Love Is Like A Red, Red Rose to which we all listened in silent transport, some of us with our eyes upturned in wistful sadness as we remembered the Joes and Jeannies of our youth. And at the end of the evening we all declared “A Man’s A Man For A’ That” as we shook each other by the hand.

That was a night, but then it always is, isn’t it.

Look, let me tell you something I heard. How Tam o’ Shanter came to be written. The tale may surprise you for many reasons. I heard the story from someone, and they heard it from someone in Ayr who heard it from someone in Mauchline who heard it from someone in Tarbolton. And that person from Tarbolton heard it from his grannie, and… well, you get the picture. Each one swears that it is a true story.

Firstly you must forget Alloway Kirk and the Brig o’ Doon. The story didn’t happen there. Imagine instead a man riding slowly along a country road, on his way to his farm at Mossgiel, his mare plodding hoof-after-hoof, he himself in a sober brown-study – aye, sober! No drunken blellum he, but a serious, sullen, frowning man, a young man who would have been handsome but for his scowl. He has come from a Lodge meeting in Mauchline where he had been passed over for advancement to one of the Craft’s arcane and worshipful positions, and passed over in favour of one more lately come to the brotherhood. However, remembering that concord should prevail amongst Brother Masons, he had transferred the resentment in his mind to other things. We may suppose his thoughts to have run somewhat along the following lines:

“Farming is a business for fools and dullards. Nothing good ever came out of a farm. Let my brother Gilbert work the farm to his heart’s content, let him whistle behind the plough, let him sow and harrow and reap and stack, let him break his back on the hard work – I have done my share of labouring since I was wee, and enough is enough! I am a poet, and I am a good one, and I should be kent as one; but no one will buy my verses. My curse on all publishers. How good it would be if there was some agency, natural or supernatural, by which poetry appeared in print on its merit alone, and did not depend on the whims and low tastes of publishers. Ah, and if I was mair kent then the lasses would look upon me and love me. Finding a love would be less of a trial and more of a sport.” And so on, and so on.

This resentment smoldered and kept hot in his mind, to the extent that he missed his way. He turned left before Tarbolton Kirk when he should have turned left at Tarbolton Kirk, but as the evening darkened he was well past the loanings to Hallrig and to Spittalside before he realized his mistake. He found himself approaching a meeting-of-ways that he did not recognize as the gloaming-light faded. He looked about him, and his frown did not improve. He was about to turn his mare round and ride back towards Tarbolton when the sound of some music reached his ears from across a field. He turned his head towards where he thought the sound came from, and for a while he could see nothing; but then there was a faint, greenish-yellow, bobbing light, as though a torchbearer was picking his way across a field. Then the light became two lights, the two became four, the four eight, and so they multiplied until it seemed as though a procession of torchbearers wound its way along the further edge of the field. All the while there was the wail of small-pipes playing a slow air in time to which the torchbearers marched.

Then their torches threw light upon some old walls and ruined towers, and upon a dour, square house of stone. The marchers passed in and out amongst the buildings, touching their torches to flambeaux in sconces, to braziers, and at last to a great bonfire, and against all this light the young man could see those walls now as squares of oblongs of shadows.

“Why this must be the old monastery ruins and castle of Fail,” he thought to himself. “But surely there have been no monks here since before the days of the Covenanters, and surely also no one has lived at the old castle – if you could call such a meager block a castle – for generations, not since the ill-reputed Laird died while old King James was still a bairn. That’s more than two centuries syne.”

Curiosity now overcame the young man’s former emotions. He looped the reins of his mare round the limb of a tree, climbed over a low stone fence, and made his way cautiously across the field towards the light and the music. The small-pipes were playing a jauntier tune now, and voices were joining in, not so much singing as chanting to the rhythm of the tune. He reached the outer wall of the monastery ruins and carefully peeked around them. What he saw made his jaw drop. His first thought was to take flight – aye and it would have been better for him if he had! There was only one word to describe the beings who had marched to that place by torchlight.

Witches!

I know, I know, that’s not a word we are supposed to use these days for fear of offending someone. Och there’s aye something to keep us from speaking the truth! Let me say then that these wights, these nighttime revelers, were as far away from the honest wiccans and pagans of today as it is possible to be. They were further still from the old storybook witches with their pointy hats and flying besoms. There is no better way to say what they were if not witches and warlocks, except perhaps that “the earth hath bubbles, as the water has, and these are of them.” So profound their evil, so eldritch their craft, so obscene their practices, so loathsome the object of their worship, so deep, so dark, so full of mortal danger…

As with all true evil, however, there was something fascinating and beguiling about them, a web of enchantment that even they wove without being conscious of it. The impulse to flee that had briefly come upon the young man died as quickly as it had appeared, and was replaced by a stronger curiosity than had first lured him to that spot. He stayed, he watched, enthralled even as disgust rose within him to battle with the thrall. The throng of this conventicle – it must have been a veritable synod of covens! – milled around a stone table, an altar dark-stained and cracked. Onto it they placed the burdens, offerings and sacrifices they had brought with them, or other foul objects wrenched from the freshly-breached tombs within those ruined walls. The young man made a ghastly catalogue of them in his mind:

A murders’s banes in gibbet-airns;

Twa span-lang, wee, unchristen’d bairns;

A thief, new-cutted frae a rape,

Wi’ his last gasp his gab did gape;

Five tomahawks, wi’ blude red-rusted;

Five scymitars, wi’ murder crusted;

A garter, which a babe had strangled;

A knife, a father’s throat had mangled…

… and so on, and so on, you know them all as well as I do, I have no doubt. When these had all been placed in a horrid tangle, the piper struck up another tune, a lively reel, and the company began to dance. The young man could just make out the piper sitting in an alcove, seven feet or more up a wall. He was a darker shadow in the dark, as though the light from the fires and torches could not reach him. Yet still the young man could tell that the piper’s fingers worked and worked at the chanter of his small-pipes, and the tune that came forth was lively, almost cheery, though there was mockery in its cheerfulness. As the witches and warlocks danced around the great table, the young man felt his own feet tapping to the tune. The reel gave way to a jig, rattling skirls and triplets rippled from the pipes, and the ghastly crowd flung themselves into their dancing, panting, sweating, shedding clothes as they whirled. Tongues lolled, eyes glazed with madness, spittle flew from their lips as the tune changed again to a wild slip-jig. One by one the witches and warlocks began to fall in exhausted stupors or trances until only a handful were left dancing, all hideous hags – except for one.

Louping higher than the rest, whirling and spinning with an uncanny vigour, her eyes bright, her face shining in ecstasy, was a young lass, stripped to her brief petticoat. The young man could not keep his eyes from her, nor his lascivious thoughts from her bare legs, or from what else might have been scarcely hidden.

“I ken her!” The sudden thought came to him. “Damn me but I ken her! That, unless I am mad, is the daughter of Brother McDowell from Mauchline. Aye, it is, it is. It’s young Nannie. Nannie whom I met at McDowell’s house on two, no, three occasions last year. Why, she must be no more than eighteen years old – and she’s here at a witch’s Sabbath?” Then he began to recall the looks that Nannie had given to him during those three visits. When he had looked at her directly she had lowered her eyes demurely, but once or twice he had caught her looking at him, just a swift, sideways glance. Now the awfulness of the scene began to lose its effect on him. Instead he looked at Nannie and saw not a witch cavorting round a horror-laden altar, but a wild thing, a beautiful thing, a filly or a young deer springing from crag to crag, an object of lust… no, of love!

All the remaining dancers except for Nannie dropped to the floor, and propelled by some new insanity the young man dashed out from behind the wall, louped into the middle of the blazing light, and seized Nannie by her hands. For a time which might have been an hour or a second, they danced and louped together in a frenzy, more a single being than two. Then –

“Weel done, Cutty-sark!” yelled the young man. “Weel done, Cutty-sark!”

Whatever spell had bound them momentarily was shattered by those words. The piping stopped. All was silence. Nannie crouched like a wild cat waiting to spring, her eyes no longer shining with the pleasure of the dance, but hard, dark, feral. All around him the exhausted witches and warlocks propped themselves on their elbows as though about to rise. Some eyes turned to the alcove where the piper sat. The young man stood, wishing he could cast a line around the seconds that had just past, haul them in, make it so they had never happened. In that moment of great peril, while all was yet still, he took hold of his chance, turned, and ran!

As he sped across the field it was only terror that made him turn his head to look behind. He caught glimpses. Witches and warlocks all in a guddle, tripping over each other in their haste, some grabbing knives and hatchets from the altar, some already running after him. At the head of the pursuit was Nannie, the hands that he had held in their dancing stretched before her like claws. No more tripping and stumbling now, they were all after him, Nannie in the van and the dark piper at the rear. The young man threw himself onto his mare’s back, whipped her and kicked her flanks with his heels, and she started away with less than a heartbeat to spare. Off she galloped, her hooves clattering on the road, the shrieking mob of witches and warlocks after her. Man, man could they run! Their devilish zeal, their anger at the disruption of their Sabbath giving them the strength and speed of a pack of hounds.

Wildly the young man rode towards Tarbolton, sometimes seeming to outdistance his pursuers, sometimes losing ground. At the outskirts of the little town, in a panic and instead of going straight on for the safety of the kirk, he slewed his mare sharply to the left and took the Mossgiel road. Och that was a mistake, as his pursuers simply louped over the hedges and fences and cut the corner. As he rode hard for the bridge over the Water of Fail they were almost upon him.

“Come on, Maggie, come on!” he yelled at his mare, and at last they won and barely passed over the key-stane o’ the brig!

Folk will tell you that neither witch nor warlock can pass over running water. It simply isn’t true. Witches and warlocks can pass over running water as well as you or I. Man and mare’s victory in this particular race was of no effect, for Nannie sprang and grabbed hold of the mare’s tail. The mare pulled up short, and the young man was thrown onto the hard ground, the wind knocked out of him. The next thing he knew was that he was surrounded by that horrid crew, and moreover Nannie was kneeling on his chest, her hands at his throat, her nails like talons digging into his flesh.

“Weel, weel, Rabbie ma doo,” she said, a grin twisting her beauty. “D’ye loo me?”

Oddly, even though he had never been so fearful for his life and for his immortal soul, the young man’s immediate thought was one of irritation. “Damn it,” he said to himself. “No one has called me by that diminutive since my late mother! Is this quine going to insult me before she kills me?”

Just at that moment the eldritch crowd parted, and the piper came and stood over him. The young man was expecting the Devil himself, and indeed that adversary might have seemed more comforting than the one who now looked down upon him. The fact that the piper was a lesser foe than Old McNiven, as we call the cloven-footed one, was not softened by the fact that he was as gruesome to look at. Let me say that he had the aspect of one who had lain a long time in his grave and who had been only lately and hastily disturbed. The young man looked at his grey skin stretched like old parchment over a wooden frame, at his eyeballs which were the colour of sour milk dribbled into ditchwater, at his lips which were eaten away to expose yellow-grey teeth, and he shuddered in total terror. The piper put his bony hands on his hips.

“Do I have the pleasure of addressing Master Robert Burns of Mossgiel, farmer?” he asked, his voice like rats’ claws on dead leaves, his breath stale and rank as the air of a disused charnel house.

“Aye sir, ye do,” answered the young man as bravely and politely as he could. “Do I have the honour of addressing Mister Walter Whiteford, late Laird of Fail?”

“Very late,” said the piper, nodding.

“Would you be so kind as to entreat Miss McDowell here to leave go of me, or I fear I shall have no breath left to address you further.”

“Your having or not having breath is of purely academic interest,” said the piper, nevertheless motioning Nannie to get off the young man’s chest. “Tonight both your life and your immortal soul are forfeit, on account of the vanity and resentment I see in you, as well as for disrupting the business of our unholy Sabbath.”

“Wait, wait,” cried the young man, still prostrate on the ground. “Give me twenty years more life, only twenty, and I swear to you I shall turn this night into one of the best-kent legends. I shall write a poem that will make Nannie as weel-kent you are yourself, Laird of Fail. Give me another twenty years of life!”

The piper-laird laughed. “You are no Doctor Faustus to be asking such favours. I’ll give you seven for your effrontery!”

“Fifteen,” begged the young man. “Fifteen, for the love of God!”

“Twelve,” said the Laird of Fail. “For the love of Satan.”

“Done!” They spat on their palms, the trembling hand of the living shook the cold, desiccated hand of the dead, and there was a ghastly leer upon the face of the Warlock of Fail. The Laird looked around at his followers with something like a triumphant smirk on his face, and as they began to titter and to grab hold of Robert Burns’ arms and legs, the relief in the poet’s mind turned to fear and panic. “My God, my God,” he thought. “What have I done?”

The witches with a “One… two… THREE!” tossed him into the air, and he screamed!

The young man seemed to awake from a nightmare at that moment, for he found himself standing at Mossgiel in front of his own farm, holding the reins of Maggie the mare. Both were sweating. Both were shivering.

Well, he was as good as his word. It took some time but if he worked hard at nothing else he certainly put his soul into his poetry. He took his own folly out of the story, set it some miles away, and made the protagonist a drunkard, but apart from that the tale we know as Tam o’ Shanter became famous amongst all his famous poems. He had his treasure upon earth, and now he has statues and memorials, and pictures everywhere, and a special day set aside for us to celebrate him. But twelve years to the day after his mad ride from the old monastery and his bargain with the Laird of Fail, Robert Burns died. He was thirty-seven.

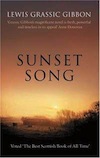

A reconstruction of the face of Robert Burns, from a skull cast made at the time of his death

You want to know his fate? The fate of Scotland’s national bard is eternal fame, of course. The fate of Robert Burns the resentful brother, the philanderer, the father of illegitimate children, the falsifier of official records, the Freemason envious of those who should have been his brothers, good heavens the Excise Man? You want to know what happened to him? I can’t tell you. No, I won’t tell you. I shall however give you a hint. There was a tall, proud ship which bore the nickname by which he had called his young, unholy dancing partner. A few years ago – mark this well – it burned!

There’s a price to pay for everything, you see.