People often ask me how I started writing. The answer is I started writing because I found I could. I entered a competition where participants had to complete a short story started by Joanne Harris. It doesn’t matter now how successful or unsuccessful my entry was; what does matter is that a quirk in my mind was turned towards writing, and I am glad of that. I thought you would like to read the story, partly © Joanne Harris, partly © me, to see the way my mind suddenly started to work back then.

In a quiet little corner of the Botanical Gardens, between a stand of old trees and a thick holly hedge, there is a small green metal bench. Almost invisible against the greenery, few people use it, for it catches no sun and offers only a partial view of the lawns. A plaque in the centre reads: In Memory of Josephine Morgan Clarke, 1912-1989. I should know – I put it there – and yet I hardly knew her, hardly noticed her, except for that one rainy Spring day when our paths crossed and we almost became friends.

I was twenty-five, pregnant and on the brink of divorce. Five years earlier, life had seemed an endless passage of open doors; now I could hear them clanging shut, one by one; marriage; job; dreams. My one pleasure was the Botanical Gardens; its mossy paths; its tangled walkways, its quiet avenues of oaks and lindens. It became my refuge, and when David was at work (which was almost all the time) I walked there, enjoying the scent of cut grass and the play of light through the tree branches. It was surprisingly quiet; I noticed few other visitors, and was glad of it. There was one exception, however; an elderly lady in a dark coat who always sat on the same bench under the trees, sketching. In rainy weather, she brought an umbrella: on sunny days, a hat. That was Josephine Clarke; and twenty-five years later, with one daughter married and the other still at school, I have never forgotten her, or the story she told me of her first and only love.

It had been a bad morning. David had left on a quarrel (again), drinking his coffee without a word before leaving for the office in the rain. I was tired and lumpish in my pregnancy clothes; the kitchen needed cleaning; there was nothing on TV and everything in the world seemed to have gone yellow around the edges, like the pages of a newspaper that has been read and re-read until there’s nothing new left inside. By midday I’d had enough; the rain had stopped, and I set off for the Gardens; but I’d hardly gone in through the big wrought-iron gate when it began again – great billowing sheets of it – so that I ran for the shelter of the nearest tree, under which Mrs Clarke was already sitting.

We sat on the bench side-by-side, she calmly busy with her sketchbook, I watching the tiresome rain with the slight embarrassment that enforced proximity to a stranger often brings. I could not help but glance at the sketchbook – furtively, like reading someone else’s newspaper on the Tube – and I saw that the page was covered with studies of trees. One tree, in fact, as I looked more closely; our tree – a beech – its young leaves shivering in the rain. She had drawn it in soft, chalky green pencil, and her hand was sure and delicate, managing to convey the texture of the bark as well as the strength of the tall, straight trunk and the movement of the leaves. She caught me looking, and I apologised.

“That’s all right, dear,” said Mrs Clarke. “You take a look, if you’d like to.” And she handed me the book.

Politely, I took it. I didn’t really want to; I wanted to be alone; I wanted the rain to stop; I didn’t want a conversation with an old lady about her drawings. And yet they were wonderful drawings – even I could see that, and I’m no expert – graceful, textured, economical. She had devoted one page to leaves; one to bark; one to the tender cleft where branch meets trunk and the grain of the bark coarsens before smoothing out again as the limb performs its graceful arabesque into the leaf canopy. There were winter branches; summer foliage; shoots and roots and windshaken leaves. There must have been fifty pages of studies; all beautiful, and all, I saw, of the same tree.

I looked up to see her watching me. She had very bright eyes, bright and brown and curious; and there was a curious smile on her small, vivid face as she took back her sketchbook and said: “Piece of work, isn’t he?”

It took me some moments to understand that she was referring to the tree.

“I’ve always had a soft spot for the beeches,” continued Mrs Clarke, “ever since I was a little girl. Not all trees are so friendly; and some of them – the oaks and the cedars especially – can be quite antagonistic to human beings. It’s not really their fault; after all, if you’d been persecuted for as long as they have, I imagine you’d be entitled to feel some racial hostility, wouldn’t you?” And she smiled at me, poor old dear, and I looked nervously at the rain and wondered whether I should risk making a dash for the bus shelter. But she seemed quite harmless, so I smiled back and nodded, hoping that was enough.

“That’s why I don’t like this kind of thing,” said Mrs Clarke, indicating the bench on which we were sitting. “This wooden bench under this living tree – all our history of chopping and burning. My husband was a carpenter. He never did understand about trees. To him, it was all about product – floorboards and furniture. They don’t feel, he used to say. I mean, how could anyone live with stupidity like that?”

She laughed and ran her fingertips tenderly along the edge of her sketchbook. “Of course I was young; in those days a girl left home; got married; had children; it was expected. If you didn’t, there was something wrong with you. And that’s how I found myself up the duff at twenty-two, married – to Stan Clarke, of all people – and living in a two-up, two-down off the Station Road and wondering; is this it? Is this all?”

That was when I should have left. To hell with politeness; to hell with the rain. But she was telling my story as well as her own, and I could feel the echo down the lonely passages of my heart. I nodded without knowing it, and her bright brown eyes flicked to mine with sympathy and unexpected humour.

“Well, we all find our little comforts where we can,” she said, shrugging. “Stan didn’t know it, and what you don’t know doesn’t hurt, right? But Stanley never had much of an imagination. Besides, you’d never have thought it to look at me. I kept house; I worked hard; I raised my boy – and nobody guessed about my fella next door, and the hours we spent together.”

She looked at me again, and her vivid face broke into a smile of a thousand wrinkles. “Oh yes, I had my fella,” she said. “And he was everything a man should be. Tall; silent; certain; strong. Sexy – and how! Sometimes when he was naked I could hardly bear to look at him, he was so beautiful. The only thing was – he wasn’t a man at all.”

Mrs Clarke sighed, and ran her hands once more across the pages of her sketchbook. “By rights,” she went on, “he wasn’t even a he. Trees have no gender – not in English, anyway – but they do have identity. Oaks are masculine, with their deep roots and resentful natures. Birches are flighty and feminine; so are hawthorns and cherry trees. But my fella was a beech, a copper beech; red-headed in autumn, veering to the most astonishing shades of purple-green in spring. His skin was pale and smooth; his limbs a dancer’s; his body straight and slim and powerful. Dull weather made him sombre, but in sunlight he shone like a Tiffany lampshade, all harlequin bronze and sun-dappled rose, and if you stood underneath his branches you could hear the ocean in the leaves. He stood at the bottom of our little bit of garden, so that he was the last thing I saw when I went to bed, and the first thing I saw when I got up in the morning; and on some days I swear the only reason I got up at all was the knowledge that he’d be there waiting for me, outlined and strutting against the peacock sky.

Year by year, I learned his ways. Trees live slowly, and long. A year of mine was only a day to him; and I taught myself to be patient, to converse over months rather than minutes, years rather than days. I’d always been good at drawing – although Stan always said it was a waste of time – and now I drew the beech (or The Beech, as he had become to me) again and again, winter into summer and back again, with a lover’s devotion to detail. Gradually I became obsessed – with his form; his intoxicating beauty; the long and complex language of leaf and shoot. In summer he spoke to me with his branches; in winter I whispered my secrets to his sleeping roots.

You know, trees are the most restful and contemplative of living things. We ourselves were never meant to live at this frantic speed; scurrying about in endless pursuit of the next thing, and the next; running like laboratory rats down a series of mazes towards the inevitable; snapping up our bitter treats as we go. The trees are different. Among trees I find that my breathing slows; I am conscious of my heart beating; of the world around me moving in harmony; of oceans that I have never seen; never will see. The Beech was never anxious; never in a rage, never too busy to watch or listen. Others might be petty; deceitful; cruel, unfair – but not The Beech.

The Beech was always there, always himself. And as the years passed and I began to depend more and more on the calm serenity his presence gave me, I became increasingly repelled by the sweaty pink lab rats with their nasty ways, and I was drawn, slowly and inevitably, to the trees.

Even so, it took me a long time to understand the intensity of those feelings. In those days it was hard enough to admit to loving a black man – or worse still, a woman – but this aberration of mine – there wasn’t even anything about it in the Bible, which suggested to me that perhaps I was unique in my perversity, and that even Deuteronomy had overlooked the possibility of non-mammalian, inter-species romance.

And so for more than ten years I pretended to myself that it wasn’t love. But as time passed my obsession grew; I spent most of my time outdoors, sketching; my boy Daniel took his first steps in the shadow of The Beech; and on warm summer nights I would creep outside, barefoot and in my nightdress, while upstairs Stan snored fit to wake the dead, and I would put my arms around the hard, living body of my beloved and hold him close beneath the cavorting stars.

It wasn’t always easy, keeping it secret. Stan wasn’t what you’d call imaginative, but he was suspicious, and he must have sensed some kind of deception. He had never really liked my drawing, and now he seemed almost resentful of my little hobby, as if he saw something in my studies of trees that made him uncomfortable. The years had not improved Stan. He had been a shy young man in the days of our courtship; not bright; and awkward in the manner of one who has always been happiest working with his hands. Now he was sour – old before his time. It was only in his workshop that he really came to life. He was an excellent craftsman, and he was generous with his work, but my years alongside The Beech had given me a different perspective on carpentry, and I accepted Stan’s offerings – fruitwood bowls, coffee- tables, little cabinets, all highly polished and beautifully-made – with concealed impatience and growing distaste.

And now, worse still, he was talking about moving house; of getting a nice little semi, he said, with a garden, not just a big old tree and a patch of lawn. We could afford it; there’d be space for Dan to play; and though I shook my head and refused to discuss it, it was then that the first brochures began to appear around the house, silently, like spring crocuses, promising en-suite bathrooms and inglenook fireplaces and integral garages and gas fired central heating. I had to admit, it sounded quite nice. But to leave The Beech was unthinkable. I had become dependent on him. I knew him; and I had come to believe that he knew me, needed and cared for me in a way as yet unknown among his proud and ancient kind.

Perhaps it was my anxiety that gave me away. Perhaps I under-estimated Stan, who had always been so practical, and who always snored so loudly as I crept out into the garden. All I know is that one night when I returned, exhilarated by the dark and the stars and the wind in the branches, my hair wild and my feet scuffed with green moss, he was waiting.

“You’ve got a fella, haven’t you?”

I made no attempt to deny it; in fact, it was almost a relief to admit it to myself. To those of our generation, divorce was a shameful thing; an admission of failure. There would be a court case; Stanley would fight; Daniel would be dragged into the mess and all our friends would take Stanley’s side and speculate vainly on the identity of my mysterious lover. And yet I faced it; accepted it; and in my heart a bird was singing so hard that it was all I could do not to burst out laughing.

“You have, haven’t you?” Stan’s face looked like a rotten apple; his eyes shone through with pinhead intensity.

“Who is it?”

I kept laughing. And then I stopped. We stood looking at each other, there in our front room, and I couldn’t find anything to say. My eyes wandered over to the table, where I had left my sketchbooks, and Stan’s gaze followed mine; then we looked at each other again, and I fancied I could see more in Stan’s eyes at that moment than I would have thought possible in such an unimaginative man. There was a sort of realisation, without understanding. There was anger, and there was pain.

I was terrified. I thought he might hit me. Then I thought he might do something to my sketchbooks. But at last he turned and went back upstairs, coming down a few minutes later in his working clothes. At the foot of the stairs he pulled his boots on, took the key to his lock-up workshop from the stand by the door, and went out of the house without saying a word or looking at me.

There was nothing for me to do, I felt, but to go back into the garden, and put my head against the trunk of The Beech.

People tell me that there was a terrible squall that night, and I am sure that the wind did get up awfully. But that can’t account for the way The Beech behaved to me. He seemed even angrier than Stan, now that our secret was out, and there was nothing slow about how he showed it. His trunk swayed, as he lashed his branches by my face, making me flinch. A falling branch glanced off my shoulder; a hail of leaves whipped my face. “Go!” he was saying to me. “Go! Go!”

Feelings of rejection and betrayal battled inside me with the sudden realisation that I had put The Beech in danger. I dashed back into the house, pulled on coat and shoes, and then I was out of the front door – leaving Daniel alone upstairs – running down towards Stan’s workshop. To Stan, a tree was nothing more than raw material, and the workshop held tools for dealing with that raw material. I knew what he wanted to do, but God knows what I could have done to stop him.

When I got to the workshop, Stan was sitting at a workbench. He was gripping the handle of a saw tightly in his right hand, but he was just sitting there, not moving. When I got closer to him, I could see that his eyes were glassy, and there was spittle running down his chin.”

Mrs Clarke sighed, and looked at me.

“That was his first stroke – the first of three. It put paid to his business, and to his dreams of a new house in the suburbs. It put paid to his power of speech, and suddenly I lived in an almost silent world, as The Beech no longer spoke to me either. We had to move after all, but into a downstairs flat at the other end of the borough. Stan couldn’t manage stairs, and in those days you looked after a sick husband, no question. He lived through the war, right into the mid fifties. I’m on my own now – Dan’s in Australia. I still draw. From memory……”

It had stopped raining, and I stood up, conscious that she had run out of steam.

“That’s quite a story,” I said. “Look, I’ll come back soon. I’ll see you again. But please excuse me, there’s something I must……..”

Not finishing sentences was catching! I looked back at her, as I hurried off towards the gate of the Botanic gardens. She smiled briefly, and then turned back to her sketchbook, and to her pictures – the pictures of our tree!

I walked home too fast for a pregnant woman. I hurried past the supermarket which stood, as I recalled, where the old lock-ups had been. I turned left into Station Road, and by the time I got to Mafeking Avenue, a street of refurbished terrace-houses, I was breathing hard. At number thirty-eight – my house – I fumbled in my pockets for the key, and opened the front door impatiently. I walked straight through the front room, through the dining room, through the nineteen-seventies’ extension, and out into the York-stone-paved back yard, with its terracotta pots and planters. I went straight down to the semicircle of earth at the far end, stopped, and looked up at The Beech. It had seemed familiar in Mrs Clarke’s drawings, but now I knew it beyond doubt. It was older, but it was the same tree.

I stretched out my hand gently, and laid it on the trunk – and began to understand! I turned, and rested my back against it, tilting my head round so that my cheek was against it too. I raised one hand to caress it, heard a sighing from the branches, and felt a few drops of rain, shaken from the leaves onto my face.

That’s where I was when my contractions started.

Twenty-five years have passed, during which time I have patiently learned the lesson which she did not: a secret has to be kept. The patience which I have learned from The Beech has spread outward into the rest of my life. The doors which had been clanging shut before, began to ease themselves gently open. My whole existence has seemed calmer, slower, more fruitful. My marriage went on, and produced a second daughter; oh sure, David left eventually, but men do that anyhow. I always meant to go and confide in Mrs Clarke, but I never saw her in the Botanic Gardens again, and eventually I found her in the municipal cemetery. The seat was a gesture to her, nothing more.

My life with The Beech has not been one of conversation, but of communion; not sex, but the meeting and merging of our essences. Oh there is passion, but it does not rage out of control. I sit with my back to him, to all intents simply a woman resting against a tree at the bottom of her garden, and I learn how to see and to feel with his slow consciousness, as it overtakes mine.

Soon – as a tree understands soon – my younger daughter Alice may well leave for college, or get married herself. But I shall never be alone. I shall be here, patiently waiting for answers. Do I carry a seed inside me? When I am dead and buried, will a new tree spring from the ground, and will its new thoughts be mine, or yours, or his own? This is the destiny of the dryad.

__________

© Joanne Harris/BBC/Marie Marshall

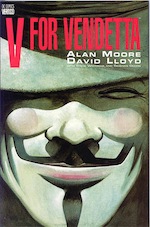

I own only one graphic novel, Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta. Of course I do – why wouldn’t I own a book in which an anarchist superhero goes mano a mano with a fascist government in Britain? I notice that Alan Moore distanced himself from the film version, exciting though that was (and it starred the wonderful Hugo Weaving!), saying that it had been ‘turned into a Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country’. Having read the script, he said,

I own only one graphic novel, Alan Moore’s V For Vendetta. Of course I do – why wouldn’t I own a book in which an anarchist superhero goes mano a mano with a fascist government in Britain? I notice that Alan Moore distanced himself from the film version, exciting though that was (and it starred the wonderful Hugo Weaving!), saying that it had been ‘turned into a Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country’. Having read the script, he said, Kick Ass is fun. It came in for a lot of abuse on account of the bad language, less for the violence – with the exception of one teenager, no bad guy is left alive by the end of the film. Its killing-spree violence is in the tradition of Peckinpah and Tarantino, subverting the bloodless wrong-righting of The Lone Ranger and Batman. I think people missed the point that it is highly satirical of the superhero genre, and simply spares no effort to de-bunk its ‘zap’ and ‘pow’ fisticuffs. It is, as the cover of the comic book says ‘Sickening violence, just the way you like it’, signaling that it does not take itself seriously and shouldn’t be taken too seriously by readers and movie-goers. The satire of the film is taken further by the character Big Daddy (Nicolas Cage) adopting the phrasing of

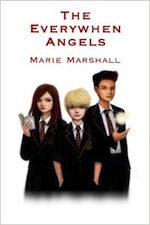

Kick Ass is fun. It came in for a lot of abuse on account of the bad language, less for the violence – with the exception of one teenager, no bad guy is left alive by the end of the film. Its killing-spree violence is in the tradition of Peckinpah and Tarantino, subverting the bloodless wrong-righting of The Lone Ranger and Batman. I think people missed the point that it is highly satirical of the superhero genre, and simply spares no effort to de-bunk its ‘zap’ and ‘pow’ fisticuffs. It is, as the cover of the comic book says ‘Sickening violence, just the way you like it’, signaling that it does not take itself seriously and shouldn’t be taken too seriously by readers and movie-goers. The satire of the film is taken further by the character Big Daddy (Nicolas Cage) adopting the phrasing of  Having fallen almost by accident into writing for young adults, I find myself skirting superhero territory. The teenagers in my novel The Everywhen Angels have powers that they don’t quite understand, and the protagonist in my recently-completed teen-vampire novella, From My Cold, Undead Hand, is a girl who has been trained to hunt and destroy vampires. Consciously or unconsciously, however, I seem to have made these characters break a mould, or break out of a strait-jacket. Unlike traditional heroes, they don’t necessarily win, they don’t necessarily triumph over a force bigger than they are, their tales do not have a clear resolution where all is explained in a neat and tidy way. Good does not necessarily triumph over evil, and where it does it may well be by accident rather than design. Why?

Having fallen almost by accident into writing for young adults, I find myself skirting superhero territory. The teenagers in my novel The Everywhen Angels have powers that they don’t quite understand, and the protagonist in my recently-completed teen-vampire novella, From My Cold, Undead Hand, is a girl who has been trained to hunt and destroy vampires. Consciously or unconsciously, however, I seem to have made these characters break a mould, or break out of a strait-jacket. Unlike traditional heroes, they don’t necessarily win, they don’t necessarily triumph over a force bigger than they are, their tales do not have a clear resolution where all is explained in a neat and tidy way. Good does not necessarily triumph over evil, and where it does it may well be by accident rather than design. Why?