I wasted a lot of time recently arguing with a blogger who had ‘learned the rules’ of English at school. My use of English was, according to him, ‘lazy’ because I broke some of these rules. No use my telling him I’m university-educated, that I have spent a lot of time examining historical texts and their linguistic usage, that I’m aware of every rule and rubric that the English language has been saddled with, and that I know full well which ones come from the natural eloquence of everyday speech and which ones were foisted on us despite that natural eloquence. No matter that I have followed and marvelled at the development of modern English from its Medieval roots to its present position as a vibrant, living World Language, with a host of attendant lects and sub-lects that handle every discourse, every social and ethnic specialness, every creative need. No, his schoolmarm knew better, and now so did he!

Aye, right.

Let me examine two of these rules and see how they stand up to scrutiny. Firstly, the question of ending a phrase or sentence with a preposition.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” says Prospero at the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the euphony of that phrase of feminine-ended tetrameter shines out of the dark of four centuries, reminding the audience of the essentially ephemeral existence of that redemptive fantasy and its characters.* Shakespeare was a genius of language; it was all he had to hold his audience with, in the days when CGI effects were not even dreamt of. And this phrase, shining like a candle, ends with a preposition.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” says Prospero at the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the euphony of that phrase of feminine-ended tetrameter shines out of the dark of four centuries, reminding the audience of the essentially ephemeral existence of that redemptive fantasy and its characters.* Shakespeare was a genius of language; it was all he had to hold his audience with, in the days when CGI effects were not even dreamt of. And this phrase, shining like a candle, ends with a preposition.

Likewise the roll-call of drowned sailors making this wonderful piece of iambic pentameter:

‘Ten thousand men that fishes gnawed upon.’ (Richard III, 1.4.25)

But I over-egg the pudding, friends. Shakespeare ended sentences this way simply because that’s exactly how everyday English – the English of Kings and commoners alike – was spoken. So when King Henry V, wandering in disguise around the camp of the English army before the battle of Agincourt, is challenged to answer the question ‘Who servest thou under?’ he does not ‘correct’ his challenger’s question. And when, in As You Like It Rosalind asks Orlando ‘Who do you speak to?’ it raises no eyebrows, because it flows off the tongue of a native-speaker like water down a country rill. Moreover, as a king may not quibble at a question, and a well-bred lady may use a preposition as she pleases, a prince may speak of ‘the thousand shocks that flesh is heir to’ in his most famous soliloquy (Hamlet, 3.1.61-62).

So, where did the rule to the contrary come from? Many consider that the attribution of Shakespeare’s usages not to one-part-observation one-part-inventiveness, but to ignorance and lack of education, started with John Dryden in the late 17c. Dryden was a scholar of Latin, and since in Latin it was impossible to end a sentence with a preposition, he decided it should be improper in English, usage or no usage.** Influential amongst his own circle though Dryden might have been, ‘Dryden’s Rule’ was not codified until the second half of the 18c, when Bishop Robert Lowth produced his A Short Introduction to English Grammar.

So, where did the rule to the contrary come from? Many consider that the attribution of Shakespeare’s usages not to one-part-observation one-part-inventiveness, but to ignorance and lack of education, started with John Dryden in the late 17c. Dryden was a scholar of Latin, and since in Latin it was impossible to end a sentence with a preposition, he decided it should be improper in English, usage or no usage.** Influential amongst his own circle though Dryden might have been, ‘Dryden’s Rule’ was not codified until the second half of the 18c, when Bishop Robert Lowth produced his A Short Introduction to English Grammar.  But even he acknowledged that ending a sentence with a preposition was dominant ‘in common conversation’ and suited ‘very well the familiar style of writing.’ So not even Lowth would go as far as saying it should never be done!

But even he acknowledged that ending a sentence with a preposition was dominant ‘in common conversation’ and suited ‘very well the familiar style of writing.’ So not even Lowth would go as far as saying it should never be done!

Nevertheless, by the early 20c it became the norm amongst teachers of English in schools to preach up the banishment of prepositions from their natural place in colloquial speech. Notwithstanding that, the preposition knew its place better than the teachers did, and kept to it in every discourse except in the speech and writings of pedants. Even Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage referred to the preposition’s banishment as a ‘superstition’!

At this point in the discussion of prepositions it is usual to cite Winston Spencer Churchill who, it is supposed, replied to a torturous memo from a civil servant, in which prepositions had been engineered away from the end of phrases to the extent that the prose resembled crazy-paving, ‘This is something up with which I will not put!’ However, nice though this piece of ridicule is, the story is apocryphal.

At this point in the discussion of prepositions it is usual to cite Winston Spencer Churchill who, it is supposed, replied to a torturous memo from a civil servant, in which prepositions had been engineered away from the end of phrases to the extent that the prose resembled crazy-paving, ‘This is something up with which I will not put!’ However, nice though this piece of ridicule is, the story is apocryphal.

So, is it actually wrong to take prepositions away from the end of sentences? Well, no it isn’t. It is no more wrong than to banish them. As in all things to do with English usage the principle guidelines*** are: clarity, i.e. there should be no confusion, no ambiguity about what is meant; euphony, i.e. it should not sound ugly; emphasis, i.e. the placing of any word depends on how the phrase or sentence is nuanced, thus to say “Where are you going from?” can be used not only because of its colloquial currency, but because it may draw attention to the most important component of the question.  Equally, when Abraham Lincoln drew the preposition away from the end of a sentence in his address at Gettysburg – ‘increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion’ – he knew precisely where the emphasis should fall in his rhetoric. Thus both are correct, in their own way, according to the context.

Equally, when Abraham Lincoln drew the preposition away from the end of a sentence in his address at Gettysburg – ‘increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion’ – he knew precisely where the emphasis should fall in his rhetoric. Thus both are correct, in their own way, according to the context.

Clarity. Euphony, and emphasis are only guidelines, however, and I can think of many reasons why, for the sake of artistic effect, even they can be (carefully) discarded.

On to the next issue, the use of the double negative.

The blogger I was discussing my usage with seemed to be too busy reading his own prejudices to read what I was actually saying about this. It all came about because I deliberately used a negative word to negate a negative phrase I had lifted from him. I was in fact using two negatives to resolve to a positive. He couldn’t get his head round that, he couldn’t cope with any idea except that two negatives together were ‘wrong’. Yet the concept of two negatives resolving to a positive is actually straight-down-the-line schoolmarm English! I’ll leave that point there, as it needs no embellishment.

There is, of course the question of using a double negative as an intensifier. Now, do I need to quote Shakespeare and Milton to anyone? It is usual for anyone who hears a usage in English that they think is ugly, ‘lazy’, or just new, to shake their head, wring their hands, and lament “Oh, the language of Shakespeare and Milton!” The thing is, both of these writers sometimes used double negatives as intensifiers. Oh yes they did!

There is, of course the question of using a double negative as an intensifier. Now, do I need to quote Shakespeare and Milton to anyone? It is usual for anyone who hears a usage in English that they think is ugly, ‘lazy’, or just new, to shake their head, wring their hands, and lament “Oh, the language of Shakespeare and Milton!” The thing is, both of these writers sometimes used double negatives as intensifiers. Oh yes they did!

Viola says of her heart, ‘And that no woman has, nor never none shall mistress be of it,’ (Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, 3.1.156-157) and actually I counted four in there!

‘Nor did they not perceive the evil plight in which they were,’ (Milton, Paradise Lost). This is an interesting example, as it has the common use of ‘nor’ as an intensifier at the beginning of a phrase. And by the way, yes, I spotted where Milton had placed his preposition. As I said, both are correct usage.

The difficulty that some readers have with such intensifiers is that, post-18c and the introduction of books like Lowth’s, their use has been identified with a lack of schooling. Whether that identification is a fair criterion to judge them is another matter. In my discussion with the blogger, I cited ‘African-American Vernacular English’ (AAVE), which is recognised by academic linguists as being a legitimate lect of English. Its usage is so ingrained, that it is not simply current but widely influential. Its origins are unclear, but it is probable that it drew its strongest characteristics not only from African speech-patterns but also from the speech-patterns of early English-American settlers. Certainly a very clear factor in its development was the generations-long deprivation of the African-American societal layer from formal education. However, in no way does that invalidate its legitimacy as a lect, in no way are its users inherently ‘lazy’ for using it. I find it highly ironic that ‘laziness’ should be an attribute so often applied to a people who for generations had to suffer slavery!

In AAVE, as I said, the use of a double negative as an intensifier is very common. So, for example, when Ray Charles sang “I don’t need no doctor…” it was perfectly clear what he meant. Again – clarity. But my stubborn blogger again could not get his head round the fact that to use or not to use a double negative depended entirely on context, not on a supposed laziness or lack of education. Certainly not on my part.

In AAVE, as I said, the use of a double negative as an intensifier is very common. So, for example, when Ray Charles sang “I don’t need no doctor…” it was perfectly clear what he meant. Again – clarity. But my stubborn blogger again could not get his head round the fact that to use or not to use a double negative depended entirely on context, not on a supposed laziness or lack of education. Certainly not on my part.

So, is my own English usage ‘perfect’? Well, should I even be aiming for that? In this essay I have deliberately used colloquial forms which have been frowned at by generations of schoolmarms. I have used the singular they/their, I have ended sentences with prepositions, I have started sentences with conjunctions, I have mixed British and American criteria for double and single quotes, I have sprinkled this essay with all kinds of things that some readers may find questionable. But did you, at any time, not understand what I was saying? I doubt it. That’s because I know my English, I know what it does, I know how it’s used, and I know how to use it.

But no, my English has never been ‘perfect’. I headed this article ‘I’m in a subjunctive mood’. That’s because I have to confess that I wrestled with a particular grammatical issue for many years – the subjunctive.

In the English language, strictly speaking, verbs no longer have a subjunctive mood. English does, however, retain a few zombie elements of it, and for a long time I had a big, big blind spot about these elements. Were I to illustrate this by saying that, if I was you, I would read no further, then you would see what I was driving at. I said ‘Were I to illustrate this…’ and that is pure subjunctive, expressing something conditional. I said ‘if I was you’, which was pointed out to me by someone editing my work as being ‘wrong’. To my mind, the word ‘if’ was enough to carry the conditional sense, and the phrase ‘if I was you’ required no subjunctive form of the verb. However, I had never been pulled up on this issue until that editorial process. I checked up on the matter, and I found that ‘if I were you’ was generally regarded as being ‘correct’. Was this another of these arbitrary ‘rules’ that had been foisted on us in the 18c? That didn’t matter to me. What did matter was the question of register and discourse – for whom I wrote generally, and in what context. In that respect ‘if I were you’ would be better received, and actually I had to admit it sounded better to my ear when I spoke each over. It sounded right. It sounded right. It had the benefit of euphony, this use of a double – ha! – conditional.

Wonder of wonders, there’s a grammatical construction that you must double.

Interestingly, though, the way it had been put to me was that ‘if I was you’ was the way the idea was commonly expressed amongst users of English as a second language, in a particular country, and was regarded by many users of English as a first language in that country as the speech of the ill-educated. And there I think we have come full-circle!

__________

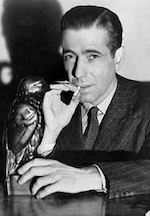

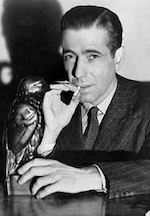

* Humphrey Bogart’s final words in The Maltese Falcon – “The stuff that dreams are made of” – is in fact a misquotation. But that isn’t a problem, because there are many, many misquotes from Shakespeare, from the Bible, from other sources, floating freely out there. The English language is not poorer for them, it is probably richer.

* Humphrey Bogart’s final words in The Maltese Falcon – “The stuff that dreams are made of” – is in fact a misquotation. But that isn’t a problem, because there are many, many misquotes from Shakespeare, from the Bible, from other sources, floating freely out there. The English language is not poorer for them, it is probably richer.

** This is precisely why splitting an infinitive used to be considered incorrect – it was impossible in Latin, so it should be improper in English. See? Modern linguists consider that to be a silly, unnecessary rule, and I’m with them!

*** Inasmuch as rules are for the blind obedience of fools and the guidance of the wise.

There’s a lot that can be said about the Burning Man festival, held every year in the Nevada desert, and not all of it is positive. But the one thing that I support is that its internal function depends on everything being free – not bought and sold, not even bartered, but free. Everything is, somehow, paid on. Now, of course I don’t attend, for many, many practical reasons, but this year I have had a remote presence. Not only did I write the script for the Guild History of I Tamburisiti di FIREnze, as posted here before, but I also provided some poetry for display there.

There’s a lot that can be said about the Burning Man festival, held every year in the Nevada desert, and not all of it is positive. But the one thing that I support is that its internal function depends on everything being free – not bought and sold, not even bartered, but free. Everything is, somehow, paid on. Now, of course I don’t attend, for many, many practical reasons, but this year I have had a remote presence. Not only did I write the script for the Guild History of I Tamburisiti di FIREnze, as posted here before, but I also provided some poetry for display there.

This year the theme is The Renaissance. I was contacted a few days ago by the Project Coordinator of ‘Camp Thump Thump’, a group that regularly attends Burning Man, giving lessons in drum-making and drumming, letting people build, play, and take away their own drums. For 2016 the group has adopted a theme based on renaissance Italy – the time of the Borgias, the Medici, and Leonardo da Vinci – and have reinvented themselves as

This year the theme is The Renaissance. I was contacted a few days ago by the Project Coordinator of ‘Camp Thump Thump’, a group that regularly attends Burning Man, giving lessons in drum-making and drumming, letting people build, play, and take away their own drums. For 2016 the group has adopted a theme based on renaissance Italy – the time of the Borgias, the Medici, and Leonardo da Vinci – and have reinvented themselves as  The Sun came to the Earth and had a child with her. That child was a field of wheat, and it grew from its mother towards its father, becoming more and more golden.

The Sun came to the Earth and had a child with her. That child was a field of wheat, and it grew from its mother towards its father, becoming more and more golden. missed. So the Sun and the Earth called upon their friends the Four Winds, and together they made seasons to nourish all that was left of the wheat-child. And eventually that single stalk of wheat became a great Tree.

missed. So the Sun and the Earth called upon their friends the Four Winds, and together they made seasons to nourish all that was left of the wheat-child. And eventually that single stalk of wheat became a great Tree.

It happened that War saw a beautiful woman, whose name was Peace. Desiring her, he took her away to live with him. But Peace was never happy, and when he asked her why, she answered that it was because she was cold, for though War is hot he can never pass his warmth on to anyone.

It happened that War saw a beautiful woman, whose name was Peace. Desiring her, he took her away to live with him. But Peace was never happy, and when he asked her why, she answered that it was because she was cold, for though War is hot he can never pass his warmth on to anyone. Keats and Chapman

Keats and Chapman were having a friendly game of quoits one day. They were neck-and-neck on points, each being as good as the other at the sport. Chapman, desperate to pull ahead, flung his penultimate quoit to the furthest peg, and ringed it perfectly. He drew back to let fly his last missile, when Keats stopped him.

were having a friendly game of quoits one day. They were neck-and-neck on points, each being as good as the other at the sport. Chapman, desperate to pull ahead, flung his penultimate quoit to the furthest peg, and ringed it perfectly. He drew back to let fly his last missile, when Keats stopped him.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” says Prospero at the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the euphony of that phrase of feminine-ended tetrameter shines out of the dark of four centuries, reminding the audience of the essentially ephemeral existence of that redemptive fantasy and its characters.* Shakespeare was a genius of language; it was all he had to hold his audience with, in the days when CGI effects were not even dreamt of. And this phrase, shining like a candle, ends with a preposition.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” says Prospero at the end of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the euphony of that phrase of feminine-ended tetrameter shines out of the dark of four centuries, reminding the audience of the essentially ephemeral existence of that redemptive fantasy and its characters.* Shakespeare was a genius of language; it was all he had to hold his audience with, in the days when CGI effects were not even dreamt of. And this phrase, shining like a candle, ends with a preposition. So, where did the rule to the contrary come from? Many consider that the attribution of Shakespeare’s usages not to one-part-observation one-part-inventiveness, but to ignorance and lack of education, started with John Dryden in the late 17c. Dryden was a scholar of Latin, and since in Latin it was impossible to end a sentence with a preposition, he decided it should be improper in English, usage or no usage.** Influential amongst his own circle though Dryden might have been, ‘Dryden’s Rule’ was not codified until the second half of the 18c, when Bishop Robert Lowth produced his A Short Introduction to English Grammar.

So, where did the rule to the contrary come from? Many consider that the attribution of Shakespeare’s usages not to one-part-observation one-part-inventiveness, but to ignorance and lack of education, started with John Dryden in the late 17c. Dryden was a scholar of Latin, and since in Latin it was impossible to end a sentence with a preposition, he decided it should be improper in English, usage or no usage.** Influential amongst his own circle though Dryden might have been, ‘Dryden’s Rule’ was not codified until the second half of the 18c, when Bishop Robert Lowth produced his A Short Introduction to English Grammar.  But even he acknowledged that ending a sentence with a preposition was dominant ‘in common conversation’ and suited ‘very well the familiar style of writing.’ So not even Lowth would go as far as saying it should never be done!

But even he acknowledged that ending a sentence with a preposition was dominant ‘in common conversation’ and suited ‘very well the familiar style of writing.’ So not even Lowth would go as far as saying it should never be done! At this point in the discussion of prepositions it is usual to cite Winston Spencer Churchill who, it is supposed, replied to a torturous memo from a civil servant, in which prepositions had been engineered away from the end of phrases to the extent that the prose resembled crazy-paving, ‘This is something up with which I will not put!’ However, nice though this piece of ridicule is, the story is apocryphal.

At this point in the discussion of prepositions it is usual to cite Winston Spencer Churchill who, it is supposed, replied to a torturous memo from a civil servant, in which prepositions had been engineered away from the end of phrases to the extent that the prose resembled crazy-paving, ‘This is something up with which I will not put!’ However, nice though this piece of ridicule is, the story is apocryphal. Equally, when Abraham Lincoln drew the preposition away from the end of a sentence in his address at Gettysburg – ‘increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion’ – he knew precisely where the emphasis should fall in his rhetoric. Thus both are correct, in their own way, according to the context.

Equally, when Abraham Lincoln drew the preposition away from the end of a sentence in his address at Gettysburg – ‘increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion’ – he knew precisely where the emphasis should fall in his rhetoric. Thus both are correct, in their own way, according to the context. There is, of course the question of using a double negative as an intensifier. Now, do I need to quote Shakespeare and Milton to anyone? It is usual for anyone who hears a usage in English that they think is ugly, ‘lazy’, or just new, to shake their head, wring their hands, and lament “Oh, the language of Shakespeare and Milton!” The thing is, both of these writers sometimes used double negatives as intensifiers. Oh yes they did!

There is, of course the question of using a double negative as an intensifier. Now, do I need to quote Shakespeare and Milton to anyone? It is usual for anyone who hears a usage in English that they think is ugly, ‘lazy’, or just new, to shake their head, wring their hands, and lament “Oh, the language of Shakespeare and Milton!” The thing is, both of these writers sometimes used double negatives as intensifiers. Oh yes they did! In AAVE, as I said, the use of a double negative as an intensifier is very common. So, for example, when Ray Charles sang “I don’t need no doctor…” it was perfectly clear what he meant. Again – clarity. But my stubborn blogger again could not get his head round the fact that to use or not to use a double negative depended entirely on context, not on a supposed laziness or lack of education. Certainly not on my part.

In AAVE, as I said, the use of a double negative as an intensifier is very common. So, for example, when Ray Charles sang “I don’t need no doctor…” it was perfectly clear what he meant. Again – clarity. But my stubborn blogger again could not get his head round the fact that to use or not to use a double negative depended entirely on context, not on a supposed laziness or lack of education. Certainly not on my part. * Humphrey Bogart’s final words in The Maltese Falcon – “The stuff that dreams are made of” – is in fact a misquotation. But that isn’t a problem, because there are many, many misquotes from Shakespeare, from the Bible, from other sources, floating freely out there. The English language is not poorer for them, it is probably richer.

* Humphrey Bogart’s final words in The Maltese Falcon – “The stuff that dreams are made of” – is in fact a misquotation. But that isn’t a problem, because there are many, many misquotes from Shakespeare, from the Bible, from other sources, floating freely out there. The English language is not poorer for them, it is probably richer.